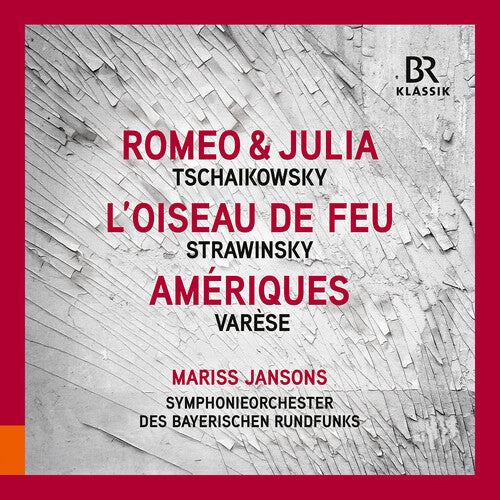

BR Klassiks

Stravinsky/ Tchaikovsky/ Varese - Ameriques

Stravinsky/ Tchaikovsky/ Varese - Ameriques

Usually ships within 1 to 2 weeks.

Couldn't load pickup availability

SKU:BRKK900016.2

Share

What made Mariss Jansons different from many of his colleagues? What was the key to his success? And most importantly, after all his artistic experiences, what brought about his maturity and artistic completion In addition to his own willpower and his work ethic, his extraordinary musical life was determined by many factors; they included an open-minded and supportive environment, and an orchestra of outstanding musicians. One important aspect was certainly the fact that Jansons despised any kind of routine. Even when rehearsing Beethoven's Eroica for the umpteenth time, he was always inspired anew by the work - discovering the as yet undiscovered. Routine would have prevented any change in his perspective, and hampered his enthusiasm. Moreover there was Jansons' meticulous and analytical approach to his work, which started long before he mounted the podium. He began by reading biographical information on the composer, scholarly information on the work, texts about it's era and it's milieu - everything he could lay his hands on. During rehearsals, he then passed on his profound knowledge and his resulting interpretive approach to the musicians. Jansons considered it his task, as early as the first rehearsal, to bring all the musicians up to the same level of knowledge. He wanted them to understand his thought processes, to recognise the explained concept behind the work and, ideally, to be able to feel the same way during their performance as he did on the podium. In the concerts, this synchronous implementation by one hundred musicians of the musical content of a work and of the concept inherent in it duly brought about that incredible pull that almost all of Janson's interpretations exert (ed) on his listeners. In addition to this collective aspect of everyone pulling together, Jansons also worked on the sound that is genuine for each composer. In this regard, for instance, he condemned accusations of kitsch where Tchaikovsky's music was concerned. He was aware of the danger of music being played too sweetly. For him, it was simply Tchaikovsky played wrongly, and was like pouring "sugar into honey". It meant a lot to Jansons to bring out the emotions in Tchaikovsky's Sixth Symphony, of course - the emotional drama, the tragedy, the depression - but he would never force, exaggerate or emphasise them merely for the sake of effect. When the Sixth is performed as sensitively as it is by Jansons, Tchaikovsky's music acquires it's true depth of meaning. "A conductor," said Mariss Jansons, "is like a director on the podium" - he analyses, stages and interprets the work. This principle, resulting from his opera conducting, was one that he transferred to the many levels of meaning in symphonic music, and here he developed a kind of directorial concept with precise approaches to interpretation. Works such as Stravinsky's Petrushka or Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique were primarily suited to this, because as programme music they sparked the visual imagination and demanded a certain musical "realism". He wanted the fairground music in Petrushka to sound shrill and out of tune, and asked the musicians to have the courage to articulate their part in just the same manner, rather than trimming it to the expectations of high culture. The contrabassoon was to play roughly, even vulgarly. Jansons was against any attempt to make the music sound pleasant here - he wanted the orchestral barrel-organ to sound out of tune, and the symphonically portrayed drunken passer-by to sound very drunk indeed. Similarly, in Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, the March to the Scaffold passes us by as a musically realistic nightmare, gripping right to the end - when the head of the executed man, severed by the guillotine, falls very audibly to the ground. Jansons also worked especially intensively on modifying the sound of the strings, above all when a phrase had to assume a subtle and psychologically important function. He differentiated playing styles very precisely in individual passages - rough, melancholy, brisk, cynical, gloating, whispering, giggling or radiant - and here he particularly influenced the bow stroke, the pressure on the string and the stroke length.