1

/

of

1

FYE

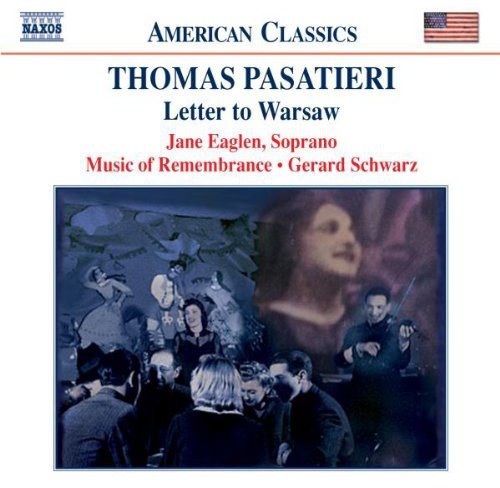

Letter to Warsaw

Letter to Warsaw

Regular price

$22.99

Regular price

Sale price

$22.99

Unit price

/

per

Shipping calculated at checkout.

Usually ships within 1 to 2 weeks.

Couldn't load pickup availability

SKU:NAAC8559219.2

Share

Daily performances at Sztuka were organized by a group of writers from the Living Journal, a satiric daily chronicle of the ghetto, written by a group of authors under the direction of Szlengel. Szpilman described these programmes as "a witty chronicle of ghetto life, full of sharp, risqué allusions to the Germans". The Sztuka was considered an elite club for the ghetto's few people of any means. First-person accounts of an evening at the Sztuka note the high quality of it's black-market coffee and caviar, and of the musical, humorous and satirical offerings. Those who could gathered for brief escape from the surrounding atmosphere of death and disease. Stepping outside meant a return to the ghetto's grim realities - the starving, diseased, and lice-infested ghetto population whose despairing cries for "Bread, Mercy, Death" quickly extinguished the Sztuka's fleeting moments of pleasure. In 1942, during the mass deportation of 300,000 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka, Pola Braun was assigned to the Ostdeutsche Bautischlerei-Werkstätte (OBW), an industrial plant, where her work helped postpone her own deportation for a period. It has not been established exactly when she was transported to Majdanek. At Majdanek she was active in the women's camp, along with other Polish political prisoners involved in the cultural life. Most of the women were from Warsaw, and many probably knew Pola Braun from before the war. Braun participated in the concerts organized by Polish prisoners from Pawiak, to whom we owe thanks for remembering and collecting some of Braun's poems. Braun was murdered on 3 November 1943, in the mass executions code-named Aktion Erntefest (Operation Harvest Festival) by the Nazis - the liquidation of approximately 42,000 Jewish prisoners from Majdanek and other concentration and labour camps in the Lublin district. Two of the six poems in this song cycle, "Jew" and "Tsurik a heym", were written during Braun's period in the Warsaw ghetto. The remaining four - "Mother", "Letter to Warsaw ", "Ordinary Day" and "Moving Day" - date from her incarceration in Majdanek. Braun sang her own songs, accompanying herself on the piano. These heartfelt songs stirred the emotions, particularly of Polish women from places other than Warsaw who identified with her message. Braun gave concerts at Majdanek in a barrack that contained furniture from the ghetto, including a piano. Several secret concerts were held there for the Jewish and Polish women prisoners. Braun's extant poetry was assembled after the war by historians. These include the Polish political dissident Aleksander Kulisiewicz, himself a prisoner in Sachsenhausen, who copied out variants of some of Braun's Majdanek pieces. Pola Braun's poems in Kleinkunst style are revealing in their observations about her surroundings, her deportation, and her Jewish identity. They open a window, especially, to the emotional life of all women caught inextricably in the web of Holocaust tragedy. Braun's voice of musical witness ensures that she will not be swallowed up by the anonymity of history. Through Thomas Pasatieri's music, her words will tell a story, and remind us that each of the victims of the Holocaust was an individual. Each had a life, a story, and aspirations beyond survival. Through this extraordinary music, we offer a tribute to the human spirit, and do our small part to honor the Holocaust's legacy.